For example, if, say, 50 new luxury units become newly available in a medium-sized market, the influx of new high-priced units will drive up average rent levels more than median rent levels. Although average rents would perhaps increase noticeably in such a case, the change would not necessarily reflect a market-wide change in rent levels. Or, if a small number of highly-desirable units raised rents considerably, this could also move the average rent up even if the larger marketplace could not bear any significant increases in rents.

So, compared to median rents, average prices are more prone to be skewed by movements in a small number of units.

Nevertheless, when speaking about general trends, it is often safe to use either average rents or median rents since the two numbers tend to track fairly closely together.

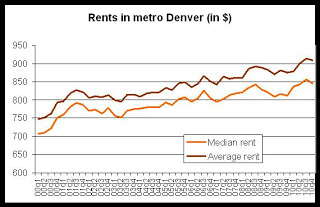

In the first graph, I've plotted metro Denver median rents and average rents together. This is from a sample size of 108,000 units. Note that median rents are lower than average rents. Apart from this, however, the movements in average rents and median rents are quite similar.

[Note: With rents, it would be an unusual situation for the median to be above the average. Since rents can't be negative, the average rent is far more likely to be skewed upward than downward. For example, rent can only dip so far below a median rent of $800 before it hits $0. On the other hand, rent can rise above the median rent level by thousands of dollars. Consequently, it is much easier for a small number of outlying rents to skew average rents up rather than down.]

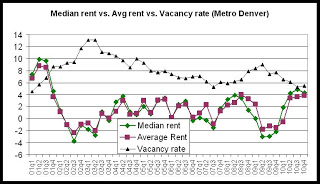

The second graph shows us that median rents and average rents also track closely together when we look at year-over-year changes in rent levels. The graph shows the percentage change in median rents and average rents for each quarter when compared to the same quarter the previous year. I've added the vacancy rate for each quarter to provide some context.

The changes in median rents and average rents tend to be nearly identical during many periods.

Theoretically, the average rent would increase more than the median rent during periods in which A-level properties are experiencing large increases, but rental units overall are not able to push rents. Or, there could be a case in which a large amount of new construction would push average rents up more than median rents since new units tend to be more expensive than older units.

It is interesting to see in the graph that during recessionary periods (2002-2003 and 2008-2009), median rents drop more than average rents in the year-over-year comparisons. This may be because higher-rent units are more insulated from the effects of recessions than are median-priced and lower-priced units. So, on the graph, the difference between the median-rent change and the average-rent change may represent a situation in which rents are dropping in most units, but a small number of high-priced units are able to maintain their rent levels even in a recessionary period. This could prevent the average rent from dropping as much as the median rent.

In a market the size of Denver, however, there are not many periods in which changes in average rents are heavily skewed from the median rent level.

There are other situations in which average rents could be skewed in relation to median rents. Please feel free to offer observations on this issue in the comments section.

0 comments:

Post a Comment